Klara Hobza • The Breathing Trilogy • 24.06.–05.08.2023

It is as much a cliché as it is a truism: life is mysterious. When it leaves a body, the change is immediate. Breathing comes to an end, the body is oddly still. Affection vanishes from the eyes, facial features dissolve. After a short while our attachment to a dead body dissipates. Every day we are confronted with the arbitrary nature of what is acceptable to eat. The only way to do this, is to continuously forget. Just as we forget what a steak is.

The willful disavowal of knowledge involved in this operation of hiding the animal origin of food requires an enormous effort, a constant suppression into unconscious rumblings and thus has far-reaching psycho-social consequences (this, ultimately, is Jacques Derrida’s point in his 2008 The Animal That Therefore I Am).

There is no pathos of this familiar kind in Klara Hobza’s film On Slaughter. A certain affection is voiced—“Little sheep, go to sheep heaven” says the human protagonist, Markus, before we hear the soft discharge of a gun—but the dominant sentiment is awe with the inside of the animal, laid bare in the course of the slaughter. The camera doesn’t shy away but neither does it claim objectivity. It does not soften the strangeness of the anatomical parts, although, oddly, there is hardly any blood visible on screen.

The film is not about slaughter, but rather about the man who slaughters. Informative, sometimes childlike, he guides us through the process. The matter-of-factness of the protagonist, and his mild manner lacks any triumphalism or glee at the killing, which makes it more bearable to watch him dismember the animal. His fascination and wonder are even infectious. Markus has a chasteness I associate with Roberto Calasso’s characterization of the archaic notion of the hunter.

On Slaughter leaves much unexplained, in fact, it refuses any narrative resolution. Partially filmed in the dark, some of the actions are hard to follow and take on something mysterious, reminiscent of shamanistic rituals. Drawing on traditional music of Yakutian heritage, Aldana Duoraan’s interspersed breathy chants invoke such a ritualistic reading of the scene in unexpected moments. But turning On Slaughter into a story—a sheep is killed and taken apart—risks betraying the subtlety of Hobza’s vision. On Slaughter’s persuasive power lies in its lack of narrative, commentary or pathos.

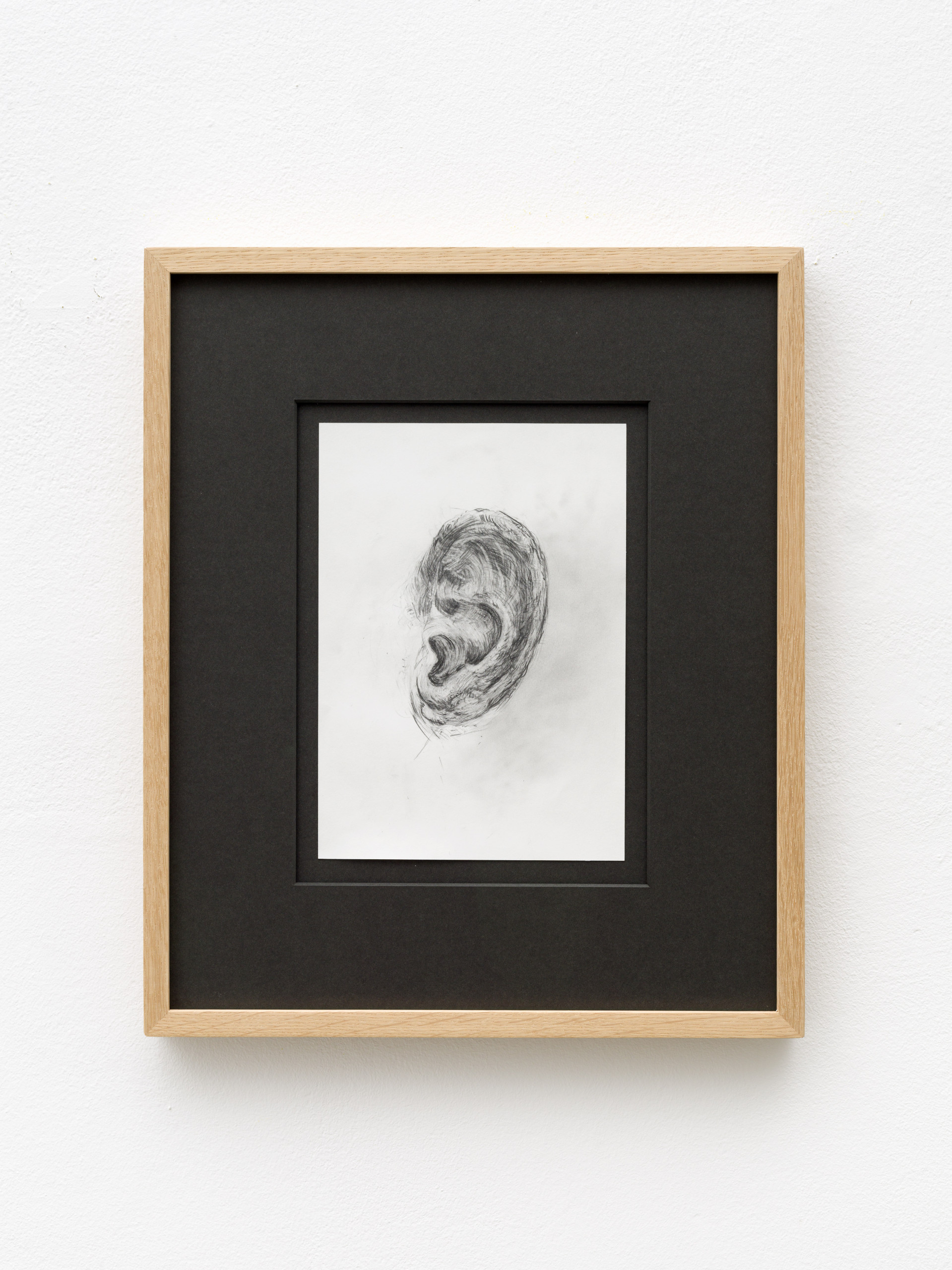

Breathing is an important motif in Hobza’s practice in general. Her most recent body of work, pencil drawings of ears Those who listen a lot, is executed using breathing techniques associated with East Asian meditation and martial arts practices. Starting in 2020, the ongoing series originated in the artist’s residency in a small town. Hobza interviewed members of the community—among them, mayor, pastor, gamekeeper, cantor—and her drawings of their left ears became portraits of a sort. While the ear has been notorious as an identifying mark—forensic anthropometry, physiognomy and biometrics have focused on its singularity, art history on its depiction—Hobza is after something else than the peculiar shape. Can the act of listening be represented?

The paper’s glossy surface, rich with graphite and labor, attests the process of drawing these dense webs, repeatedly erasing and overdrawing. Fine lines appear to caress the ears’ serpentine shapes with their gnarly peaks and valleys. Foremost a manifestation of the encounter of pencil and paper, it is not the works verisimilitude that is in the foreground but the process of their creation. The drawings capture movements and experiences of the artist: it is both the conceptual rigor and the authenticity of their production, the presentness in the moment of creation, that gives these works their resonance.

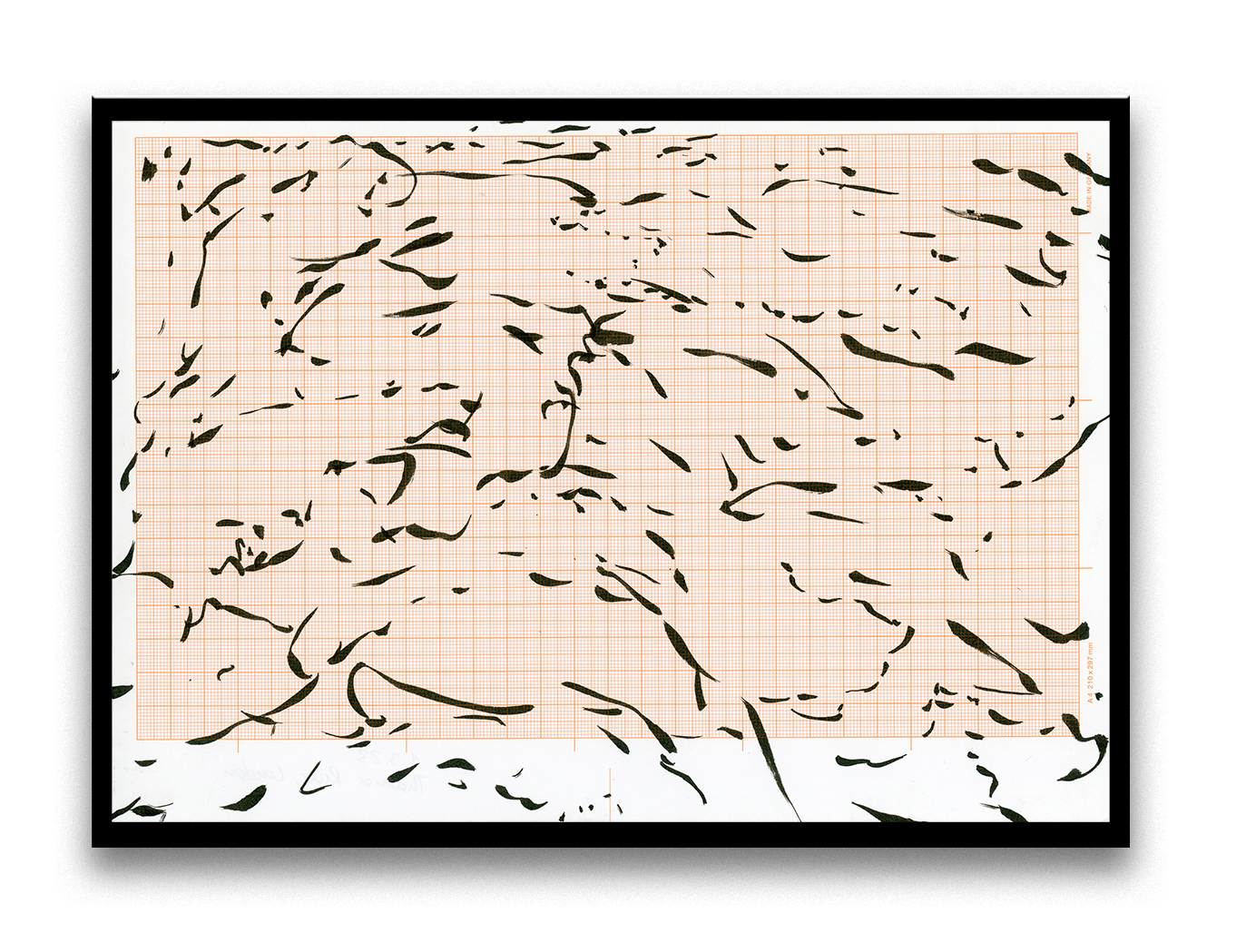

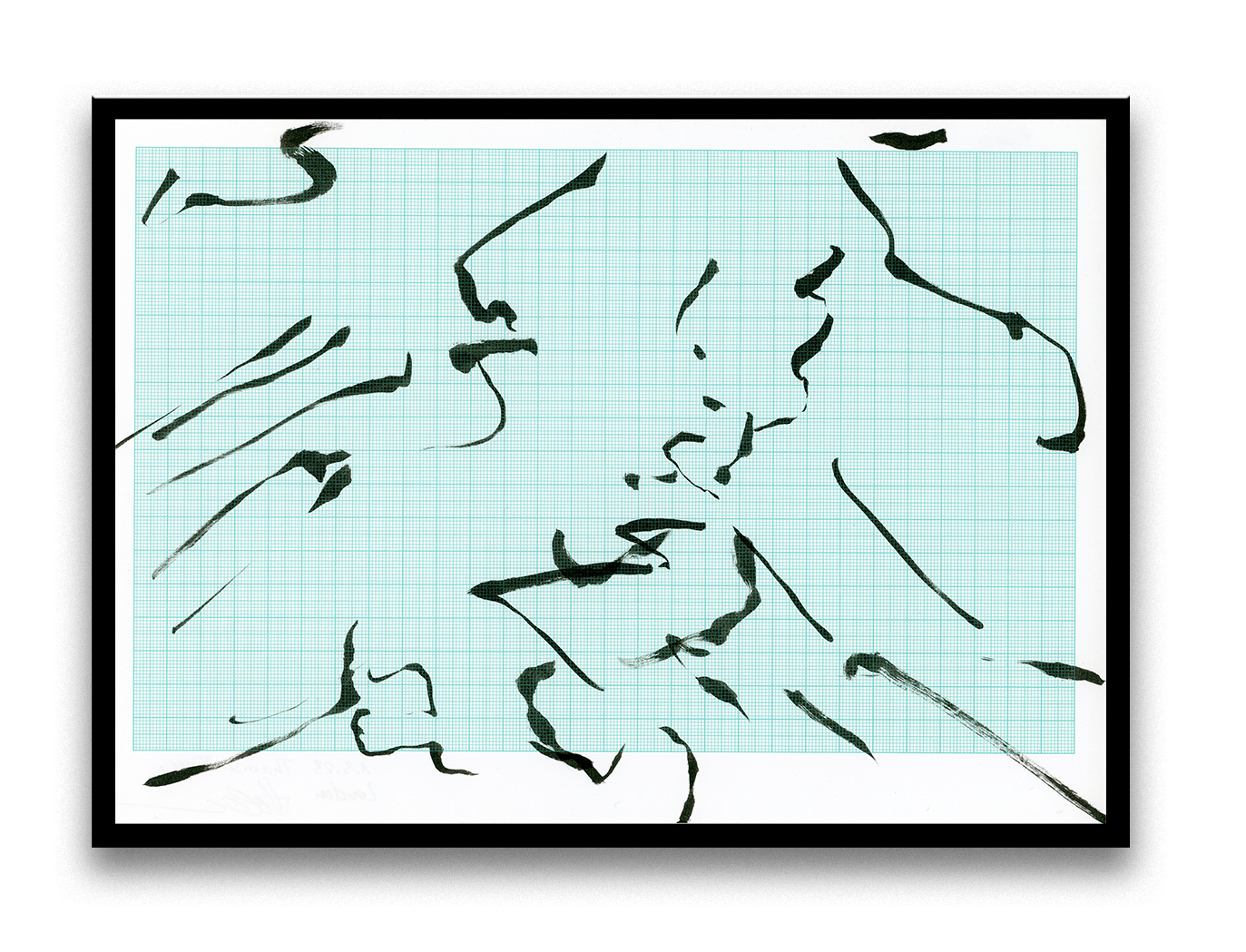

This is equally true for the third body of work on view in the exhibition, River Studies. Since 2017 Hobza has made hundreds of quick sketches of rivers. Executed in ink on graph paper, the suggestion of a scientific notation of objective data on the gridded lines plays against the loose brushstrokes that cover the sheets. Recalling abstract pattern or calligraphic writing, they also made me think of maps tracing ocean currents or winds. While breathing plays a crucial role in the execution of these works—here too Hobza employs a breathing technique of ritualized attack and defense movements from martial arts for her mark making—the work is indebted to another instance of breath control: diving.

A near-death dive during her wildly ambitious project Diving Through Europe (since 2010), changed her relationship to water. Overcoming the traumatic experience by understanding the movement of currents became a gesture of banning their power. However, interpreting River Studies as a kind of coping mechanism reduces them to a narrative content which is precisely what the artist is refuting in her work. Rather the series speaks to the larger significance of what art is to Hobza: a way to make sense of the world. The result is not spectacle, an anecdotal thrill, but a generative creative process—not trauma but the process of overcoming it, as artwork. The anti-narrative stance of Hobza’s work does not allow the viewer (or herself) to succumb to the easy reassurance of the comforts of storytelling.

The Breathing Trilogy speaks to being present in the moment, facing the world courageously and honestly, even to our complicity in the death of other beings. As such these works are a consistent continuation of Hobza’s conceptual performative projects: imaginative, grandiose and full of radical optimism for the human condition.

—Isabelle Moffat