Shahin Afrassiabi • Spirit Level • 02.12.2022–28.01.2023

Not for the fast read

On the paintings of Shahin Afrassiabi

By Jan Verwoert

Modern cities teach people to become avid readers: to get ahead, you must keep up with what the news say, how stocks react, what the word is on the streets, and which colors and cuts are current this season. Such metropolitan literacy is a powerful tool. It teaches you the power to perform a fast read on all that you see. Applied to the arts, it gives you know-how needed for coding work, so it will be read in accordance with your intentions. Rendering art ready for reading is a must in an urban arena of competitive literacy.

Fatigue, however, tends to set in just as fast, when you consume life as if it were a stream of information. Why tire yourself out that way? Stopping to read isn’t easy. Not after you trained your brain to read and filter, decode and detect messages in the text urban life writes, every day, all around you, as you, and everyone around you, struggle to stay afloat, on top of the script, and abreast of the plot. Your nervous system at this point will be hard-wired into the selfsame circuits that keep traffic lights synchronized, news updating, inboxes filling up, and GPS tracking your steps.

Instead of a quick exit there is inevitable exhaustion. Sooner or later it sets in, when the senses are done reading. Before shutting down, however, they might briefly switch to a different mode: a strange clarity at the cusp of exhaustion. You’re still fully alert, and wide open to the world, but no longer computing sensations, processing them as script. It’s a state of mind as much as it is a physical condition, and its expressions might be many. The wide-eyed empty stare of a tired traveller could be a sign of this alacrity beyond literacy. It’s the look that may come into your face after realizing that your connection is delayed by so much time it’s no use awaiting travel updates, for there won’t be any anytime soon. It’s a state of suspense, not meditation. But it doesn’t have to be painful. On the contrary, it could very well announce the end of a bad period, the advent of something new, and transition to a fuller sense of life. In The Man of the Crowd (1840), Edgar Allan Poe associates this state with convalescence, the state in which, after being ill, you would be out for the first time, in a café, gazing at life on the street, looking at nothing specific, because everything feels particular, as the senses are revived by input, affirming that life goes on, a bare fact, exhilarating as such that requires no further reading into, computation or commentary.

It is this state of mind that Shahin Afrassiabi’s paintings put you into. So if you say yes to this, the works may induce the particular condition of heightened awareness arising from the momentary suspension of the need to perform a fast read.

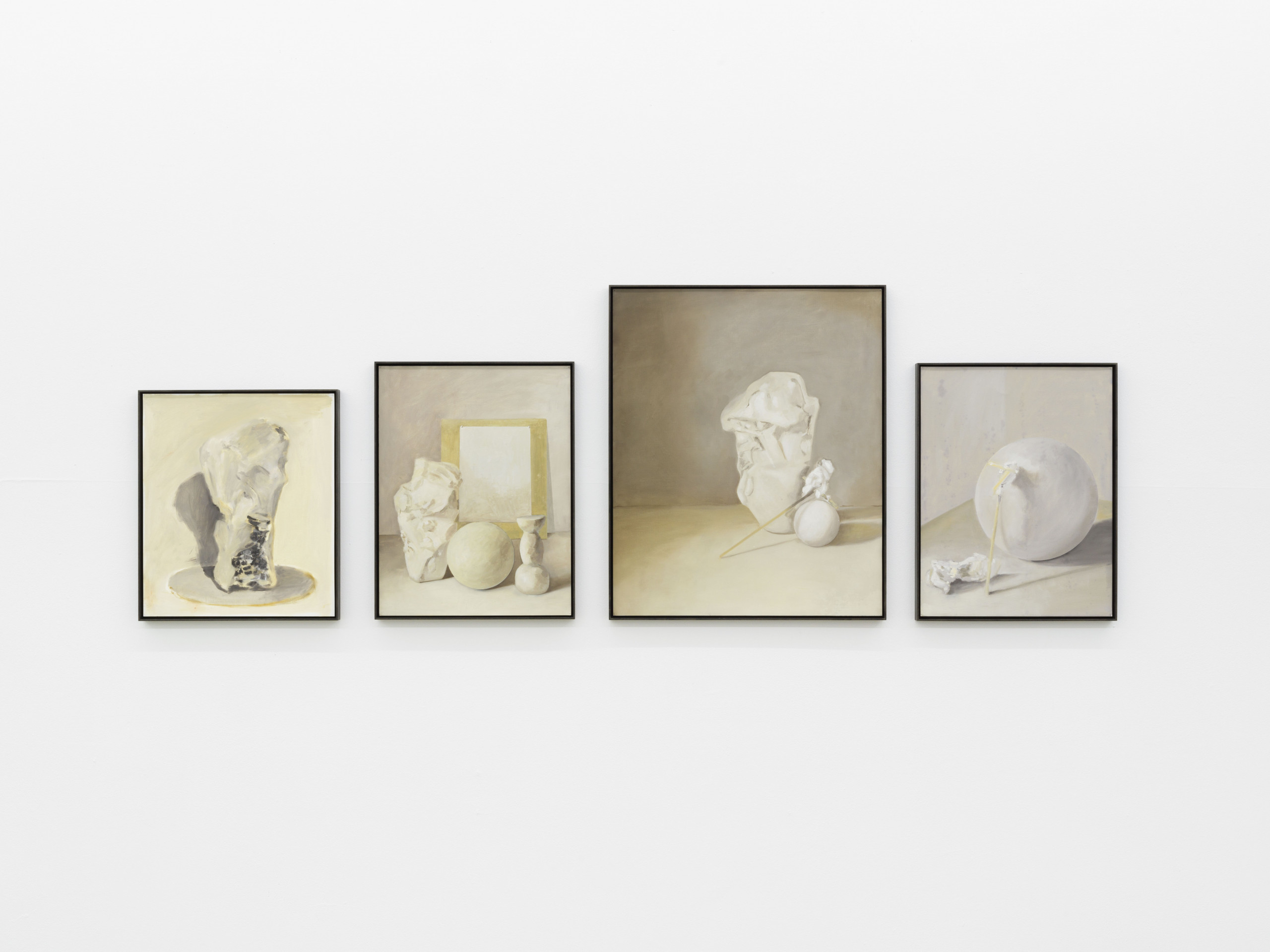

The things Shahin Afrassiabi paints and how he paints them, attract and arrest the gaze: elementary shapes, soberly depicted, in muted colors, mostly shades of eggshell and plaster white, waste no time entering your mind, by way of primary Gestalt recognition, that is, when you look you don’t have to think, as you just know what you see is: a ball, a stick, a sphere, a drawing board, a crumpled bit of what should be paper, a candleholder, a jar and a thing akin to a jug or vase in volume and proportion, but solid and jagged, like eroded rock, wood, or bone. Recognized, as they will immediately be, in their bare simplicity, the objects, their arrangement, and their calm painterly rendering tell your mind to be at ease, and your gaze to lay down its arms, and quit its inquiries. Nothing to penetrate with interpretation here, no riddle to crack, or surface to be pried open, for meaning to be hauled from unseen depths. No, relax, the things on view are what there is to see, and rest your eyes on.

It’s not like this calm would really be comforting either, though, at least not just and only. Something profoundly eerie remains, lingering in Afrassiabi’s paintings: At first, what you see seems quite real. Nothing is overtly spectral. Still, something inconspicuously uncanny resides in how things openly reveal their bare outlines and volumes, yet casually conceal what substance they may be made of. Fundamentally they leave you in doubt as to what, beyond their disarmingly simple appearance, the may actually be, and where their gathering is taking place: household objects assembled in physical space? Compositional components (circles, lines, geometrical bodies, textures and tones) arranged on the picture plane? Or emblematic ciphers — vessels of embodied meaning — organized within a symbolic microcosm? The ontological uncertainty created by Afrassiabi’s paintings is as deep as the manner in which they create it is discreet.

In inheriting the unassuming ways of dislodging reality Giorgio Morandi fostered in his paintings, Afrassiabi too suspends the difference between material and model: Like with Morandi, you can never be certain if what he paints from is an actual thing, or already a thing modeled after that thing, so no ball, jug or vase, but a piece sculpted to resemble a ball, jug or vase, seemingly so, or not, as in the case of the jagged stub, failed imitation, as it may be, of a jug or vase, from solid matter, cracked in the kiln, broken by use, or never completed in the first place. A world modeled artfully after simple things, may possibly be much further removed from literal simplicity than any fanciful drama. For, in the latter, all props, smoke and mirrors, in effect (and in terms of their function to produce said effect, and said effect only) will be strikingly literal. In a world removed one crucial, yet decisive step from actuality, however, nothing is. And this minimal, yet profound removal is rendered tangible in the multiple different nuances the otherwise near monochrome tonalities of eggshell to plaster white take on in Afrassiabi’s paintings.

In painting, traditionally, the act of removing objects from the sphere of the literally given goes hand in hand with the operation of relegating them to the sphere of the symbolically legible. Some say that such acts of relegation is what religion is about: practical customs of unplugging worldly things from their physical settings, and lifting them up onto a plane of metaphysical significance, rendering them legible to the discerning eye of those religious about literacy (i.e. those proud of their power to read and eager to put it to the test) in the process of their translation from silent earthly into talkative heavenly matters.

Insofar as the artifacts in Shahin Afrassiabi’s paintings seem modeled on and hence set apart from their physical counterparts, they would appear to become clear contenders for a transcendent status. Yet, his paintings strictly abstain from supplying any further cues, or contextual information that would establish a referential framework for transcendental reading: No heraldic signs, sacred animals, mythical figures, or suggestive inscriptions of any kind indicate which frame of reference or symbolic cipher, if any, should be applied to decipher what the model objects in the paintings might signify. In this sense, one vital characteristic of Afrassiabi’s paintings is that they simultaneously extend and suspend the invitation to read what is given-to-be-seen in them. At large, this double move could be understood as a way of exiting the economy of metaphysical literacy, and carve out spaces where eyes exhausted by religious eagerness to read into things may rest, recover, and revive their ability to see. Specifically, however, it matters which genre Afrassiabi chooses for extending and suspending the invitation to the visually literate to drop their inquisitive gaze. He’s doing still-life painting.

In still-lives the need for reading certainly lingers. Insofar as Afrassiabi taps the tradition of still-life painting — by training his eye on arrangements of mundane objects that (at first sight) look like they could be found around the house — what is given-to-be-seen might strike you as also given-to-be-read.

After all, still-life paintings conventionally are understood to be ripe with symbolism, as each and every element in the composition holds the potential of embodying an attribute of the life lived, and death to be reckoned with, in the household where the objects on show are from. Social status, heritage, and affluence would be rendered legible by the display. Plus, if the still life included books, musical, mathematical, nautical or other scientific instruments, it would in fact be literacy itself the painting could be found to advertise, namely that of the painter and the person who commissioned the piece. If there ever was an art-form purely designed to work as a handshake between the religiously literate (i.e. those eager to exercise literacy) it might be the still life: The engineer of its symbolism, and the proprietor of the know-how needed for its decoding would, via the transaction of making and purchasing the painting, affirm a mutual sense of belonging to the circle, guild, or elite endowed with the power to read. A vital twist Afrassiabi gives to the art form he adopts therefore lies in taking an otherwise ostentatiously readerly genre, and draining the reading out of it. The handshake of literacy won’t happen. That deal is off. What takes its place?

Perhaps art has a chance of entering the scene that is set when the emphasis on literacy is removed. By art I mean a certain fluency in articulating what lies dormant in the relations between particular forms, tones, textures, and weights, on the side of its makers, matched by a fluency in adopting specific modes of receptivity, in step or synch with a work’s mode of address (e.g. switching to tango, when tango is played). I’m not saying that this can be easily done. Literacy will get in the way of fluency. It’s faster. Before you know it, you will already have read the work. Unlearning the technique, and relinquishing the power of the fast read might not be a feat to be achieved at will. Leaving the city for the country, à la Thoreau, won’t make you less of a reader-writer. There is no simple fix. There is just time, to be spent, in the presence of forms, tones and textures revealing relations, not in a sphere reserved for themselves (which would be art, art only, and who knows if art is even an option among the already literate), but on the threshold, perhaps, between fluency and literacy.

Shahin Afrassiabi’s paintings delineate that threshold. They inhabit it. In spending time with them, you might sense the veil of literacy lift momentarily, and enter that eerie space between languages where there neither is any coded symbolism for avid readers to latch onto, nor some literal realism to take its place and supply factual visual information. Call it a scene of suspended isms. Art might be waiting in the wings. Still the scene remains tangibly untainted by nostalgia for a return of and to art, in dramatic fashion. With the need for fast-reading isms defused, time is set free for gazing at the (models of) things assembled in the paintings. But perhaps this time isn’t infinite either. Ragged and somewhat exhausted by use, as some of these (models of) things appear to be, they also relay a sense of finitude. The window of timeless looking will close again, in time. Things end. People forget. Some things come back to you sometimes, though. Perhaps just basic things. To know how to not miss that moment is an art in its own right, and this knowledge radiates from the heart of Afrassiabi’s paintings.